South Sudan

When Tunda Henry's family fled the civil war five years ago, the idea was that they would soon return to South Sudan. But as progress on the peace deal stalls, he now fears his family will never return.

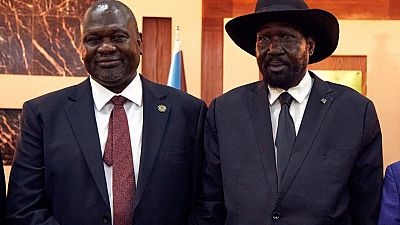

Tuesday marks the second anniversary of the formation of a government of national unity between President Salva Kiir and former rebel leader Riek Machar under the agreement signed in 2018.

Since then, the country has faced crisis after crisis, battling hunger, climate disasters, inter-ethnic violence and political rivalries. And some clauses of the peace agreement remain unfulfilled, leaving many citizens, such as Tunda Henry, disillusioned.

"I am not happy," says this father of five, the only one in the family who has not fled to Uganda. In Juba, where he lives, Tunda Henry, 40, lives in fear and does not dare to go to his village. "People disappear on the way," he says of his region, where rebel groups such as the National Salvation Front (NAS) - which has not signed the peace agreement - are still active.

Political wrangling

Meanwhile, political wrangling is undermining the gains of the peace agreement, with Machar and Kiir unable to agree on the creation of a unified army that would bring their once-enemy forces under a single command.

With less than a year to go before elections, South Sudan, which has only been independent since 2011, is at risk of sliding back into war, the UN warned in February. Between 2013 and 2018, five years of civil war have claimed nearly 400,000 lives and forced millions more to flee their homes.

To get by financially, Tunda Henry, 40, works two jobs at once: as a teacher - paid 35,000 South Sudanese pounds ($80) a month, more than half of which goes towards his rent - and as a motorbike taxi driver. "My salary is not enough to live on (...) I have to rent a house, I have to send money to my family," he says.

Corruption

Despite its oil-rich soil, South Sudan's economy is suffering, particularly from corruption among the political elite. In September, the UN accused its leaders of stealing tens of millions of dollars from state coffers.

South Sudan is ranked as one of the most corrupt countries in the NGO Transparency International's index and is heavily dependent on international aid: according to the United States, 75% of its population needed humanitarian aid by 2021.

Moreover, 80% of South Sudan's 11 million people live in "absolute poverty", according to 2018 World Bank data, and nearly two-thirds are severely hungry. International donors, who provide hundreds of millions of dollars in emergency aid each year, have refused to pay for the costs incurred by the peace agreement, angering the government.Political will

"Many of the points are not being implemented simply because we lack funds (from) the international community," South Sudanese Information Minister Michael Makuei told AFP in a telephone interview. "Most countries have done nothing (...) instead, they decided to impose an arms embargo on us which has made it difficult (to unite) our forces," he added.

For their part, international observers are frustrated by the lack of political will shown by the South Sudanese leaders in the implementation of the agreement. "There is of course donor fatigue," Christian Bader, the European Union's ambassador to South Sudan, told AFP. "Some have been disappointed. Some have observed that the money they have sent to the country has never produced the results they hoped for."

Internal conflicts

After years of procrastination, hopes are slim that a government plagued by internal strife will make significant progress before elections next year.

"I believe the peace agreement will be extended for about one or two years while government officials agree to implement the remaining clauses," says Boboya James, an analyst at the Juba-based Institute for Social Policy and Research (ISPR).

The authorities must "ensure that there is a constitution, a unified army, a judicial system and an electoral process," he adds. Until then, Tunda Henry, who did not plan to be permanently separated from his family, is prepared for a long wait.

Go to video

Almost 300 killed in wave of violence in Sudan’s North Kordofan

Go to video

ICC warns of a dire humanitarian crisis in Sudan as the war rages on

02:35

Central African Republic's major rebel groups to disarm, dissolve

01:05

Ethiopia's mega-dam on the Nile is "now complete", Prime Minister says

01:39

Sustainable development financing conference opens in Seville

01:49

Sudanese refugees in Chad face deepening humanitarian crisis