Ethiopia

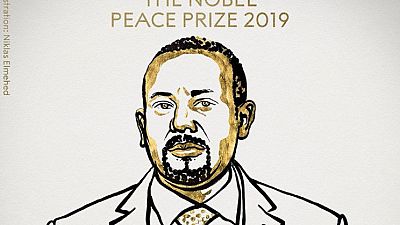

Ethiopians and Eritreans along the two countries’ shared border have misgivings about the recent award of the Nobel Peace Prize to reformist prime minister Abiy Amhed.

Ethiopia’s charismatic leader was given the prestigious prize earlier this month, partly for his role in signing a peace deal with Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki in July last year.

The peace deal effectively ended decades of hostilities, and unleashed a flurry of activities including resumption of direct flights, re-connecting telephone lines, re-establishment of diplomatic presence in the two countries and re-opening the borders.

However, hardly a year Hardly a year after Ethiopians and Eritreans celebrated the peace deal, Eritrea closed the border points at Serha-Zalambesa, Bure – Assab and Om Hajer-Humera, without giving its neighbour any official explanations.

In this article, we look at the views of residents of the borders about Abiy’s Nobel win, informed by the progress or lack of it in implementing the peace deal.

What the peace deal promised

When Abiy first reached out to Eritrea last year, he stunned observers by agreeing to accept a 2002 UN boundary ruling that Ethiopia had long rejected.

The ruling would transfer some villages and towns from Ethiopian to Eritrean territory, and would split the ethnic Irob community in two.

The demilitarisation of the border, especially on the Ethiopian side, is the main benefit of peace cited by most people in the region.

It has permitted some Ethiopians to cross for weddings and funerals in Eritrea with little harassment from the security forces.

What the peace deal has failed to deliver

Zaid Aregawi, an Ethiopian national told AFP the story of her her brother Alem, who is languishing in jail across the border in Eritrea. She says the fact that Alem was arrested without explanation, when he was carrying wood for an Eritrean businessman is proof that the peace deal has yet to be fully realised.

“If there is no free movement from both sides, what is the point of the peace deal?” she asked in an interview with AFP. “They say there is peace, however we have got big problems along the border.”

Yosef Misgina, an official in the town of Dawhan, says he receives regular reports of Ethiopians being detained, jailed and beaten in Eritrea, often after they are caught transporting construction materials and other goods.

Among them were 13 traders who were taken into custody just days before Abiy won the Nobel, two of whom remain behind bars.

Residents of Ethiopia’s northernmost villages complain of a lack of progress on demarcating the two countries’ shared 1,000-kilometre (600-mile) border.

Eritrean refugees, who still cross into Ethiopia by the hundreds each day, according to the United Nations, note that peace has not moderated the behaviour of Isaias, widely considered one of the world’s most repressive leaders.

What went wrong?

Nearly everyone laments that bilateral relations hinge on meetings between Abiy and Isaias, with little input from people on the ground.

“We can say that peace is stuck between the earth and the sky,” said Ahmed Yahya Abdi, an Eritrean refugee who has lived in Ethiopia since the war.

“When Abiy went to Eritrea he flew to Asmara, but he didn’t implement peace here, at the border between the two countries.”

Yosef attributes the detentions to continued ambiguity about the status of the border.

While the main crossings were opened shortly after the peace deal was signed, they have all since been closed, with no word on when they might reopen.

“Now we are asking that peace be institutionalised,” Yosef said. “If it is institutionalised it cannot be disrupted by individuals.”

An even bigger source of anxiety for the region is the border demarcation process, which so far has gone nowhere. It is unclear what is holding up demarcation, but many analysts suspect Eritrea is dragging its feet.

“I would say that the Eritrean government probably wants to take things a little bit more slowly because the rapprochement has implications for the domestic situation in Eritrea. It has been a closed country for 20 years,” said Michael Woldemariam, an expert on the Horn of Africa at Boston University.

Deserved Peace Prize?

Abiy’s attention is currently consumed by ethnic and religious clashes that broke out last week in the capital Addis Ababa and Ethiopia’s Oromia region, leaving nearly 70 dead and highlighting divisions within his ethnic Oromo support base.

Meanwhile, hundreds of kilometres north, frustration with his Eritrea deal is mounting in cities and towns nestled among the steep escarpments of Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region — the area most affected by the 1998-2000 border war and the long, bitter stalemate that followed.

For refugees like Sebhatleab Abraha Woldeyesus, who crossed into Ethiopia a few weeks ago, waiting for change from Eritrea seems futile, meaning true peace along the border is likely to remain out of reach.

“As a human being I don’t accept this Nobel prize,” he said. “We don’t see the peace. Abiy and Isaias, they haven’t brought it.”

01:14

Boeing reaches settlement with man who lost entire family in 737 MAX Crash

01:13

China and Ethiopia reaffirm alliance at meeting on sidelies of BRICS summit

Go to video

Kenya set to surpass Ethiopia as East Africa’s largest economy in 2025 – IMF

Go to video

World Food Programme to halt aid for 650,000 women and children in Ethiopia

Go to video

Ethiopians mark Easter with calls for peace and love amid ongoing conflict

02:19

Ethiopians in Washington D.C. keep ancient language and orthodox traditions alive