Eritrea

The ongoing standoff between the Eritrean Catholic Church and the government becomes the latest conflict between church and state on the African continent.

The church has condemned this month’s seizure and closure of its health facilities, saying it is worried about the impact it will have on Eritreans who used the medical facilities.

The church wrote a letter to the country’s health ministry, arguing that providing social services cannot be interpreted as opposition to the government.

“The government can say it doesn’t want the services of the church but asking for the property is not right,” the letter read in part.

Government on Thursday defended its decision to take over the health facilities, describing the move as a ‘mere transfer of operational modality’.

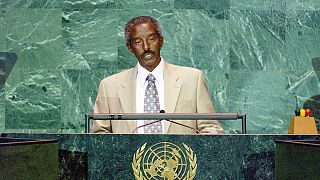

“The notion that this will negatively affect “or endanger” delivery of health services is far-fetched and simply not true. In the first place, the issue at hand is the mere transfer of operational modality,” read part of a statement issued by the Eritrean Permanent Mission to the United Nations in Geneva.

The Catholic Church in April called upon government to implement reforms as a means of countering migration to Europe, and experts believe the government is retaliating.

In its letter, the church also said that the seizure of properties could not happen in a country where rule of law existed.

Eritrea, which has been under president Isaias Afwerki since its independence from Ethiopia in 1993, has been consistently criticised for violating human rights and running a repressive state.

Roman Catholics make up about 4% of Eritrea’s population, and are only one of

four religious groups allowed to operate in Eritrea, along with the Eritrean Orthodox, Evangelical Lutheran and Sunni Islam groups.

DRC’s powerful Catholic Church

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the powerful Catholic Church became the most visible opposition voice to president Joseph Kabila during his 17 years in power.

The Church mediated between opposition groups and the government, often chastising Kabila for his government’s human rights abuses and deployed at least 40,000 observers across the country in the recently concluded national elections.

The elections which were eventually held in December 2018 were made possible by the New Year’s Eve Agreement signed on 31 December 2016. The agreement signed between the opposition and the ruling coalition was facilitated by the Catholic Church after the African Union had failed to resolve the political crisis.

The church wields considerable power in a country where over 90% of the population identify as Christians.

ALSO READ: DRC Catholic Church fears Kabila will remote-control TshisekediBurundi’s church vs Pastor-President

In Burundi, the Catholic Church has taken on the messianic president Pierre Nkurunziza who believes he is chosen by God to rule the country.

When Nkurunziza declared his intentions to seek a controversial third term in 2015, the Catholic Church opposed the project. The church also withdrew its support for elections in 2017 and and directed its priests who served on the electoral commission to withdraw their services.

The church in Burundi has historically opposed excesses and human rights abuses by the government, and paid a high price that has seen high ranking officials like the Archbishop and a Vatican envoy murdered.

Religion’s mediation role

Indeed, across the continent, the church has played a mediation role in several conflicts, including in Benin, Togo, Zimbabwe, Cameroon and Ivory Coast.

In April this year, Pope Francis, the leader of the Catholic Church globally, met with South Sudan’s leaders including president Salva Kiir and rebel leader, Riek Machar, imploring them to choose peace and heal divisions in the world’s youngest nation.

READ MORE: Will a papal kiss truly reconcile Kiir, Machar?South Africa’s Anglican bishop Desmond Tutu became famous for his role in the struggle against apartheid in the 1970s. He called out the racist regime in Pretoria and was persecuted for his preaching that compelled the world to empathise with the plight of black South Africans.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission that he chaired in 1995, which granted amnesty to perpetrators of human rights abuses during the apartheid regime, has been replicated in many countries, becoming a model for managing post-conflict scenarios.

01:07

DRC: More than 300,000 civil servants eligible to new retirement plan

01:01

Trial of DRC's former Justice Minister Constant Mutamba postponed for two weeks

00:55

The Democratic Republic of Congo celebrates the centenary of Patrice Lumumba's birth

01:52

In Goma, solar power brings light and hope in Ndosho neighbourhood

01:11

Burundi calls on United Nations to recognize 1972 genocide against Hutus

01:32

Catholic Pope affirms priest celibacy, demands 'firm' action on abuse