Former Ethiopian prime minister, Hailemariam Desalegn has blamed the archaic colonial agreements over the use of the Nile waters for the prevailing stalemate his country has with Egypt.

Egypt and Ethiopia are at loggerheads over the construction of the Grand Renaissance Dam, a $4 billion-hydroelectric project that Cairo fears will reduce waters that run to its fields and reservoirs from Ethiopia’s highlands and via Sudan.

In an interview with Sudanese-British billionaire businessman, Mohammed Ibrahim, Desalegn lamented that while Ethiopia contributes most of the Nile waters, policies developed by colonial powers limit its use of the same water.

“There cannot be any resolution on the dam issue in five words. Many people don’t understand that Ethiopia contributes 86% of the Nile waters and was told that they were not allowed to use a single drop. This was a policy developed by the colonial government” said Desalegn.

He added that during his time as prime minister, he advised the former Egyptian president, Mohamed Morsi, not to politicise the issue.

“I told Morsi not to politicise this issue this is a technical issue. Ethiopia cannot be restricted by a colonial treaty because Ethiopia was never colonised”

The last round of talks between the three countries held at the beginning of this month failed to resolve differences over the dam.

Addis Ababa denies the dam will undermine Egypt’s access to water. Ties between Egypt and Sudan were strained when Khartoum backed the dam because of its need for electricity.

With Ethiopia signaling it may start filling its towering $4 billion Grand Renaissance Dam this year, safeguarding scarce Nile water resources has surged to the top of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s policy agenda as he begins a second term.

Following are some of the frameworks governing the use of Nile river waters:

The 1929 Nile Waters Agreement

This agreement was signed between Egypt and Great Britain, which represented at the time Uganda, Kenya, Tanganyika (now Tanzania) and Sudan. The document gave Cairo the right to veto projects higher up the Nile that would affect its water share.

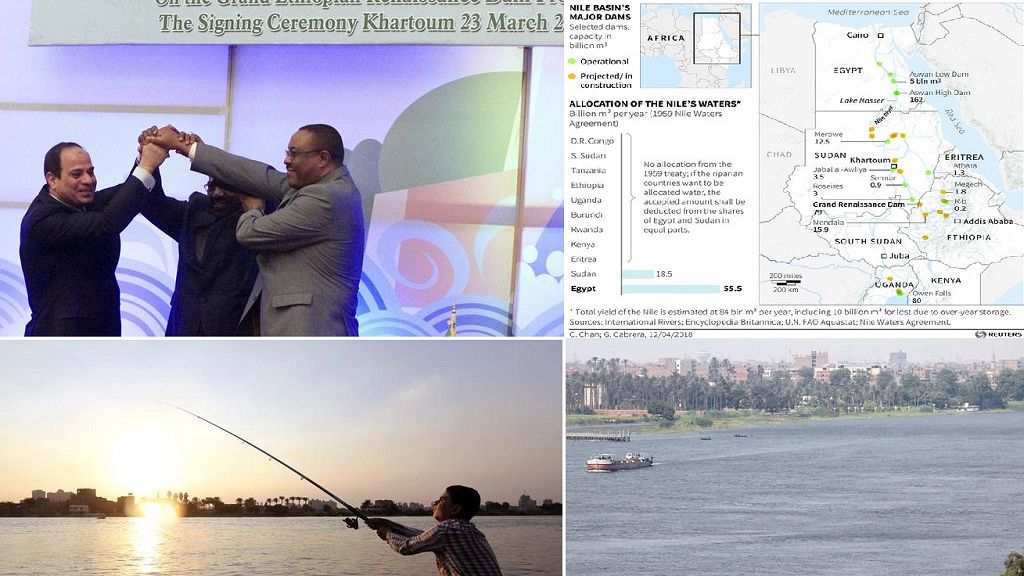

The 1959 Agreement between Egypt and Sudan

This accord between Egypt and Sudan, supplementing the previous agreement, gave Egypt the right to 55.5 billion cubic meters of Nile water a year and Sudan 18.5 billion cubic meters per year.

Both the 1929 and 1959 agreements have created resentment among other Nile states and calls for changes to the pact, resisted by Egypt.

The Nile Basin Initiative

Formed in 1999, the initiative brought together the then nine Nile Basin countries to develop the river in a cooperative manner, share substantial socioeconomic benefits, and promote regional peace and security.

The nine Nile Basin Initiative countries were Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda. Since then South Sudan has been added to the initiative.

Entebbe Agreement

Egypt froze its membership in the Nile Basin Initiative in 2010 after some upstream countries signed the Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA). Egypt has argued that the deal reallocated water shares without its approval.

The CFA, also known as the Entebbe Agreement, has been signed by six out of the 10 Nile Basin Initiative states. The signatories are Uganda, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Tanzania, Kenya and Burundi.

Egypt wants an alternative to the agreement, which now allows other Nile basin countries to conduct projects along the river without its prior consent.

The 2015 Declaration of Principles

Leaders from Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan signed a cooperation deal in 2015 over the Grand Renaissance Dam in a bid to ease tensions. The deal was meant to pave the way for further diplomatic cooperation. The main principles in the agreement include giving priority to downstream countries for electricity generated by the dam, a mechanism for resolving conflicts, and providing compensation for damages.

![[Explainer] Colonial agreements governing Nile waters can't stop Ethiopia – former PM](https://static.euronews.com/articles/461205/400x225_461205.jpg)